by Lindy Lindell

by Lindy Lindell

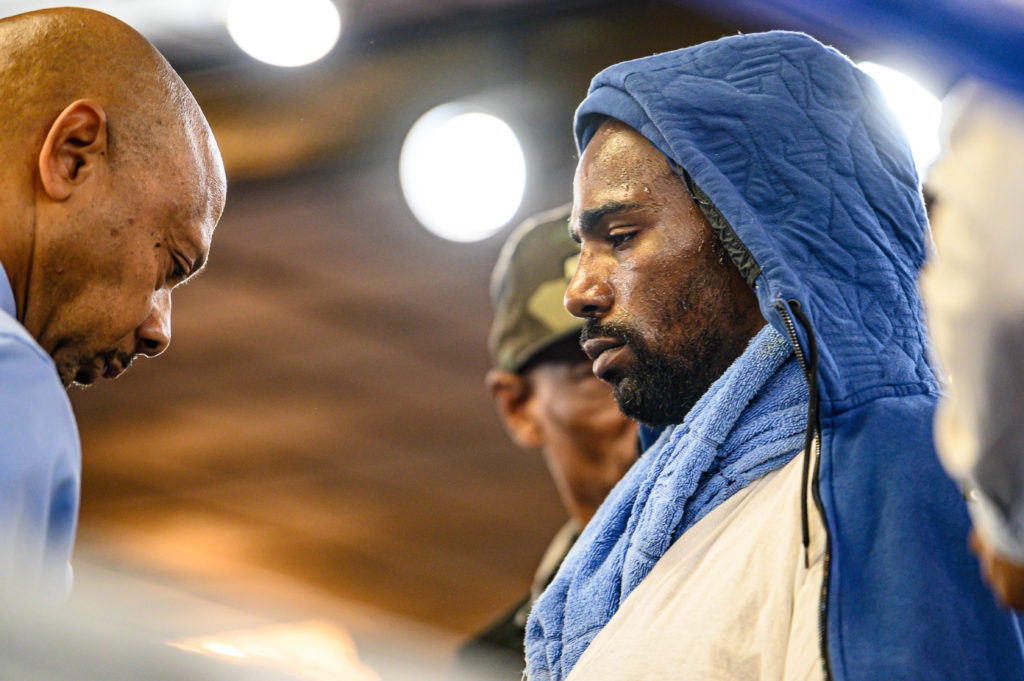

October 11, 2019, DeCarlos Convention Center, Warren, MI. Inactive for 15 months, super-middleweight Anthony Barnes, supported by Kara Ro in his corner, returned with a credible and un clear-cut six-round split decision duke over Kenneth Council. It was clear-cut, though one judge had him losing, not unreasonable, but the margin of that score clearly made it into the “ridiculous” category.

In improving to 12-0, Barnes, in a stop-start career built mostly on softies (I told him after one of his soft touches that I was going to petition the commissioner to see that he get credit for only a half-win after he blew away a stiff in less than a round at Masonic Temple several years ago). Council, after the fight, told reporter Brad Snyder that he intended to go down two weight divisions for future fights. I’m not sure that anyone has done that since Archie Moore did it more than a half-century ago, but that’s what he said. Council hadn’t fought in four years.

Save for the Barnes fight, the others were paid for by the managements/promoters of the winners. That’s four out of five fights were paid for. Sometimes it is necessary for managers to pay for fights so their fighters can get work. It is a part of boxing that everyone in the game engages in. Until a dozen years ago, I made some fights that were paid-for fights – Not many – one here and maybe another a year or two later. When one makes fights, as a matchmaker or a booking agent, one does this occasionally–and I mean very occasionally. In forty years of boxing that I observed only two boxers pulled “upsets”–and I made one of those. The manager of a welterweight named Robinson paid me $100 to bring in an “opponent” from Chicago, and that guy knocked out Robinson. There were no hard feelings because I had told the manager that the guy from Chicago “could punch a little bit.” The Chicagoan hit the Detroit fighter a good one and Robinson never fought again; he knifed someone on a bus and went into the clink for that maleficence.

The paid-for boxers all lost–that is four out of the five–fights were paid for. Not paid to lose, mind you. The opponents seemed to try as hard as they could; they just didn’t have the talent to win. When Dutch Leonard called me up for some background dope in putting together his 2002 novel, Out of Sight, he wanted to know how to handle a fixed-fight situation in which a character was going to take a dive in the fourth round, but crossed “The Boys” and headed to the canvas in the second round. He did this because that character, in pulling the double-cross, high-tailed to Michigan. I said, “Dutch, you’ve seen too many boxing movies from the 1940s. You don’t have to pay a guy off to have him take a dive. You just bring in someone who can’t win.” Leonard took my word for it, and wrote what I had said into his novel, practically verbatim.

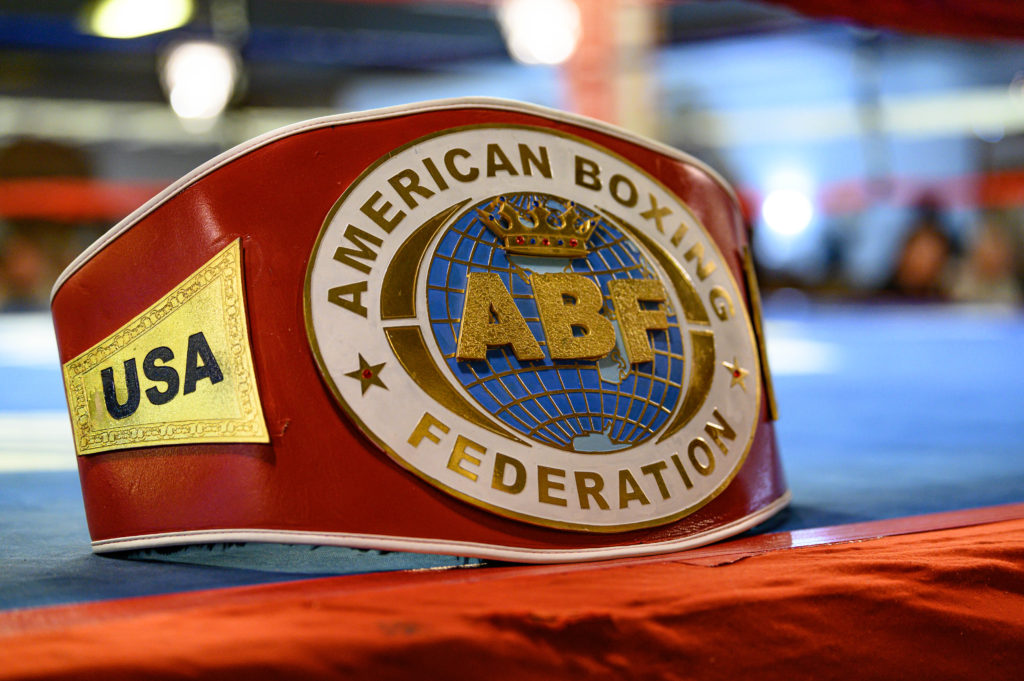

The paid-for fighters at this show all won, though Charles Dallas (1-1) fought hard before losing a majority decision to Antwan Jones, (4-0), Toledo. Rashio Evans (0-2) was blown out in one by Rolando Vargas, Milwaukee (4-0). In a lightheavyweight contest, Michael Moore, a Cleveland lightheavyweight, 18-3, won something called the American Boxing Federation, by belting out Detroit-area’s Alex Hilores, 18-9. in three when Hilores’ corner tossed in the towel. I could not help remember when a much-younger Hilores fought savagely in losing a decision in Ada, Michigan to Wade Tolle in 2003. Some 40 days after the Moore fight, Hiloros was again stopped, this time in Detroit by 45-year-old Darryl Cunningham. It wasn’t that Hiloros didn’t try. He gave it his all.

Finally, in the main go, Flint’s Andreal Holmes, a goonishly-tall welterweight, made his second straight main-event appearance on a Vi Tran show and won a virtual shutout over Walter Wright, 17-8. The problem here was (1) that the fight was originally scheduled for six rounds, and (2) it was bumped up to eight. As was the case two months before when Holmes fought the frustrated and comparatively diminutive Lenardo Tyner, Holmes is so much taller than his foes and he is so unwilling to engage in the danger zone of being hit back and his fights become exercises in futility for his opponents. When my companion heard the news that the fight had been jacked to eight rounds, he said, “Jesus, watching Holmes is like watching paint dry.”

Take-away for the evening: Anthony Barnes is back, and if he wasn’t scintillating, he showed decently. Time will tell whether or not better opponents can be afforded so that real fights can be made. But this is the second fight card in a row that has been blighted by paid-fors and if Vi Tran can go back to just having her matchmakers throw in the locals against other locals and out-of-towners who will fight back in competitive fights, fans will be treated to the kind of show she put on last February with Saginaw’s Ernesto Garza, 10-2, drilling out a game Jeno Tonte, 9-5, in the main go of a card that featured no-name locals fighting no-name out-of-towners, however, it was a show that featured action that had the fans’ blood pumping through their veins.

Featured Photo Gallery by Fred Culpepper

Photo by Bob Ryder, Fightnews.com Photo by Bob Ryder, Fightnews.com Photo by Bob Ryder, Fightnews.com Photo by Bob Ryder, Fightnews.com Photo by Bob Ryder, Fightnews.com